Summary

Entomophagy (eating insects for food) is sometimes proposed as an alternative to factory farming because it has lower environmental impact. But entomophagy is not necessarily more humane than factory farming of livestock all things considered, and along some dimensions it's actually worse, because it involves killing vastly more animals per unit of protein. Rather than promoting insect consumption, let's focus on plant-based meat substitutes.

A version of this article was published as a chapter (pp. 82-89) in What Should We Eat? (At Issue) by Greenhaven Press.

Contents

Introduction

Entomophagy has been proposed for environmental and food-security reasons, particularly in the developing world.

!['fried Grasshoppers on a market in Bangkok.' By Thomas Schoch [CC-BY-SA-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fried_grasshoppers_in_Bangkok.jpg](/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Fried_grasshoppers_in_Bangkok.jpg)

However, the idea of eating insects for food is becoming more mainstream in Western countries as well, particularly among trendsetting, ecologically conscious consumers.

Entomophagy is already widespread in many poor countries. In this piece I focus on proposals to introduce entomophagy to developed countries, because here eating insects rather than plant-based protein is a luxury, not a dietary necessity by the world's poor.

Why insect farming may cause more suffering than livestock farming

The number of insects required to produce a single meal is orders of magnitude higher than the number of chickens or especially cows required to produce that meal. Even if we give insects less moral weight per individual than bigger animals, when we sum over all the insects involved, the total suffering to produce a meal adds up to a big amount.a For example: "One would have to eat about a thousand grasshoppers to equal the amount of protein in a twelve-ounce steak." I suspect one reason people don't mind eating insects as much as livestock is that people picture a single insect and think, "Meh, that little thing isn't very important. So I'm ok with eating insects." But they forget to add up all the insects that go into their food, which collectively look more like a big animal than a tiny one.

In addition, insects may inherently suffer more than large animals if they have higher mortality rates. I don't have good data on mortality rates on insect farms. Presumably mortality rates are lower than in the wild, because farmed insects theoretically have more food, fewer predators, less disease, etc. That said, some insect farmers may not monitor conditions very closely, so it's likely that sometimes the farmed insects fare poorly. "A Bug's Life: Large-scale insect rearing in relation to animal welfare," section 3.3.6, discusses instances of high mortality rates from various diseases.

Of course, wild insects probably have even higher mortality rates, and this is a main reason why I'm concerned about the vast amounts of insect suffering in nature. But even if farmed insects potentially live better lives than wild insects, this doesn't make it right to bring more of them into existence if their lives are still on average bad.

Living conditions

Some argue that farmed insects enjoy pleasant lives: "Insects raised in farms live in teeming dark conditions (preferable environment), with ample and abundant food supply, no natural predators, no risk of outside diseases or parasites [...]." However, some insect-farming operations have nontrivial mortality rates. And farms occasionally lose almost all their insects to disease.

Egelhoff (2015) reports that Big Cricket Farms "suffered a setback when a cricket paralysis virus hit the facilities over the winter, killing 90 percent of the livestock".

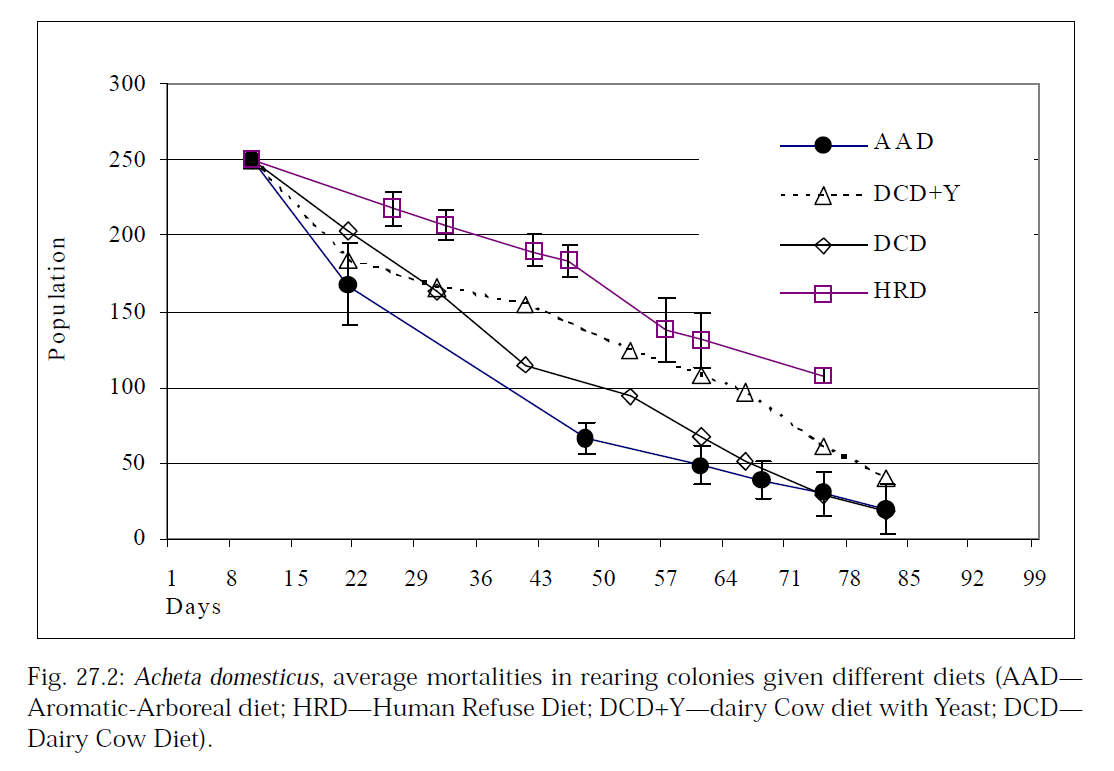

Collavo et al. (2005) examined four possible diets for the common house cricket. The following graph shows the number of survivors remaining over time for each feed type.

Even the best diet (HRD) had only 47.5% survival by day 61 (p. 521). This was just an experimental study, so maybe mortality could be reduced by further optimization of farming practices. But at least these findings illustrate the fragility of insects and the ease with which they can die prematurely.

Oonincx et al. (2015) measured survival rates of four insect species fed various diets. As reported in Table 3 of the study, survival rates were all over the map, from 6% to 93%. Most of the diets were experimental, so it may be most fair to focus on the "control" diets, which represent more tried-and-true ways to feed insects. The following table copies survival rates for control diets from Table 3 of Oonincx et al. (2015). Yellow mealworms had four different kinds of control diets, so four numbers are reported.

| Species | Survival rate (%) |

|---|---|

| Argentinean cockroach | 75 ± 21.7 |

| black soldier fly | 75 ± 31.0 |

| yellow mealworm | 84 ± 9.9 34 ± 15.0 93 ± 9.3 88 ± 3.1 |

| house cricket | 55 ± 11.2 |

Compared with the control diet, the experimental diets for house crickets led to even lower survival rates: between 6% and 27%. Oonincx et al. (2015) explain regarding house crickets: "survival rates can be considered low in this species on all diets, with the possible exception of their control diet (55%). Older studies report that [...] survival can be up to 80%. A more recent study reports survival rates similarly low (24–47.5%) as our study. These differences might be attributed to the [...] densovirus."

A survival rate of 75%, which applied to the Argentinean cockroach and the black soldier fly, means that for every three insects that does well enough to develop to the point of harvest, one fares so badly that it doesn't even make it to that point.

As a point of comparison, survival rates for US broiler chickens were 95% in 2018, although they were 82% in 1925 (National Chicken Council 2019). Maybe present-day insect farming is comparable to early 20th century poultry farming in terms of how much techniques have been optimized. Of course, even 5% mortality is too much, and the 95% of broiler chickens who survive to slaughter age still have abysmal lives.

Like farmed insects, factory-farmed pigs, chickens, and cattle also benefit from abundant food, security against predation, and so on. So why is their welfare still poor? It's because most farms don't want to spend too much effort on maintenance or optimal welfare. It pays to cram animals into smaller spaces, allow some rate of disease and illness in order to cut costs, and so on. While some small-scale insect farms may be aiming to avoid this outcome, it's not clear that in the long run the entomophagy business wouldn't go in a similar direction as the livestock business. Maybe if the insect-eating demographic is more liberal/eco-conscious/etc., it would push for more humane raising conditions, but the same is true if that demographic were eating livestock. (Note that I don't necessarily think small, eco-conscious livestock farms are more humane, because their slaughter methods may be worse than at factory farms due to lack of pre-slaughter stunning.)

In this article, cricket farmer Kevin Bachhuber says: "I'm super Jewish, and the crickets are not kosher, but a lot of kosher law involves humanity to your animals." Probably some other current insect farmers care about humane treatment as well. But in the long run, once the entomophagy industry grows and faces pressures to cut costs when supplying bulk quantities of insect protein to big food corporations, it seems likely that these high ideals will be lost. Perhaps PETA or Mercy for Animals will one day conduct undercover investigations that reveal neglected crickets and sadistic mealworm farmers at factory insect farms of the future.

Oonincx and de Boer (2012) explain: "Over the last two decades productivity of chickens and pigs has increased annually by 2.3%, due to the application of science and new technologies [29]. Further improvement of the mealworm production system by, for instance, automation, feed optimization or genetic strain selection is expected to increase productivity and decrease the environmental impact." However, selection for increased growth has caused significant welfare problems in pigs (p. 5) and chickens. Perhaps selective breeding of insects will also lead to welfare problems. Of course, this isn't all bad, since more yield per animal means that fewer animals need to be killed. But it would be better if we didn't have to make this tradeoff between "worse welfare per animal" vs. "more animals killed" at all.

What about do-it-yourself insect farmers? It's hard to say for sure, but these might be worse than big farms. Lots of amateurs might try an insect farm in their basements and in one way or another cause immense suffering—whether by forgetting to water the insects, or starving them, or not sealing the container and causing an insect infestation in the rest of the house. My family used to raise worms for composting, and the number of times we accidentally killed the whole worm batch in a gruesome way was more than one. The experience is not uncommon: "Louie tried her hand at vermicomposting, composting with earthworms, and 'totally killed them.'"

Even if living conditions in insect farms were perfect and there was no accidental mortality, there would still be 100% mortality when the insects were slaughtered. Unless slaughter were painless (which it often is not; see the next section), the farmed insects would still experience extreme suffering after a short period of life, which I think would make their lives net negative. People who care about preference frustration or other moral values besides experienced welfare may also object to slaughter on other grounds, even if it were painless. I think we should avoid framing the debate merely in terms of whether living conditions are good, because there's also the inherent problem that all the insects die not long after being born (except maybe a few kept around as breeders and whatnot).

Slaughter

The Wikipedia article on "Welfare of farmed insects" has a helpful section discussing how insects are slaughtered—in developing countries, commercial farms, and by hobbyist insect eaters. I won't repeat that information here.

!['Fried silkworm [no, scratch that] (misidentified: I think some kind of bean grub) sold by a street vendor in Jinan, China.' By Steven G. Johnson (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fried-silkworm-china.jpg](/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Fried-silkworm-china.jpg)

Many of the inhumane ways in which insects are killed involve heating—boiling, frying, steaming, roasting, etc. This is probably extremely aversive. Insects have heat sensors and display avoidance in response to hot stimuli. In fact, even the simple C. elegans nematode (not an insect) avoids heat, and its escape behavior is modulated by opioids, just like in humans ("The effect of opioids and their antagonists on the nocifensive response of Caenorhabditis elegans to noxious thermal stimuli").

Sometimes insects are eaten alive, such as in the case of casu marzu, a cheese that "contains thousands of live maggots". In cases like these there's not even a pretense of humane slaughter. In Mexican cuisine, chinicuiles (red maguey worms) "are sometimes eaten alive and raw" and "are also considered delicious deep fried or braised"; all of these ways of dying sound awful.

Environmental considerations

Entomophagy is usually sold as more environmentally friendly than eating cows and pigs. (Environmental benefits relative to chickens are less clear.) Of course, it's not obvious why promoting entomophagy is more effective at environmental conservation than promoting plant-based meat substitutes, which are already abundant and much less resisted on "ickiness" grounds. (Even in vitro meat is plausibly less "icky" than insects, and certainly regular plant-based meat products are.) In fact, I suspect the ickiness of entomophagy is part of the appeal for some people: It seems like a cool, countercultural thing to do, with much more impact to onlookers than just saying "I'm vegetarian." Of course, some entomophagy advocates do genuinely care about the cause on its merits, and I respect that stance.

One might argue that the additional grain fed to livestock requires killing massive numbers of insects on crop fields, so that the total insect death toll may be higher from eating bigger animals. This may be true, but it's not clear to me that crop cultivation is net bad for insects in the long run. In fact, growing crops, in some cases, plausibly prevents more insect deaths than it causes.

Finally, it's not obvious how big the environmental gains are for do-it-yourself insect farmers. Growing insects requires a fair amount of work for a relatively small output, and growers may need to buy grains/fruits/vegetables to feed the insects, though food scraps can also contribute to home-raised insect diets. More food needs to be fed to insects than what comes out, and if that feed comes from cultivated crops, it's not true that entomophagy reduces crop cultivation relative to eating veg.

This page reports: "Farm-raised snails are typically fed a diet of ground cereals." Another page elaborates: "The diet may consist of 20% wheat bran while 80% is fruit and vegetable material. Some growers use oats, corn meal, soybean meal, or chicken mash." So it looks like farm-raised snails are fed a lot of human-edible food.

Oonincx and de Boer (2012) studied the environmental impacts of mealworms produced by "a commercial mealworm producer in The Netherlands (van de Ven Insectenkwekerij, Deurne, The Netherlands)". "The quantities of all inputs and the output of the production system were disclosed by the mealworm producing company." The mealworms were fed "fresh carrots and a mixed grain feed (i.e. wheat bran, oats, soy, rye and corn supplemented with beer yeast)." The authors report: "The feed conversion ratio (FCR) for concentrates (kg/kg of fresh weight) for the mealworms in this study (2.2) was similar to values reported for chicken (2.3) [...] [28]." While mealworms had lower global warming potential than chicken or milk (Fig. 2), they had higher energy use than chicken and milk (Fig. 3). The authors explain: "Mealworms, being poikilothermic, depend on suitable ambient temperatures for growth and development. When ambient temperatures are low, heating is required, increasing energy use."

One study "found crickets that were fed a poultry-feed diet showed little improvement in protein conversion efficiency, compared to the industrial-scale production of broiler chickens, which are foul reared for their meat." And what about feeding food waste to insects? "99 per cent of crickets fed on food waste and diets composed largely of straw, died before reaching a harvestable size, proving that they can’t simply be fed waste to create cheap food."

Memetic impact

A number of animal activists see one of the worst consequences of meat production as being the indirect effects that animal farming has on society's attitudes toward animals in general. When people eat animals, cognitive dissonance makes it harder to simultaneously care about them ethically. A number of studies have explored this point, including "Don't Mind Meat? The Denial of Mind to Animals Used for Human Consumption."

The same arguments apply in the case of insects. If society is going to eventually take seriously the plight of quintillions of insects in nature, it would help if its citizens didn't have a vested interest in ignoring insects' simpler but still morally important forms of sentience.

The entomophagy movement appears to be growing at a ferocious pace in 2014. The idea of eating insects has an edge to it that makes it an attractive story for news outlets and a tempting way for eco-minded consumers to show off (even though eating vegan would probably cause less environmental impact). I'm very worried where this situation will end up.

Why insect farming probably increases insect populations

Insect farming is bad because it forces huge numbers of animals into short lives that end with plausibly painful deaths. However, natural habitats also contain large numbers of invertebrates that die painfully not long after birth. If insect farming displaces some natural insect habitat, does it actually increase total insect numbers?

I suspect that insect farming probably does significantly increase insect numbers, although I welcome more rigorous calculations on this point. Following is one simple analysis. Let's compare two possible human diets:

- Humans could eat corn directly. Suppose that this requires 1 hectare of land, and 1 hectare of land is left over for native vegetation.

- Humans could eat insects who have been fed corn. Because there's some loss of energy due to insect metabolism, suppose it requires 2 hectares of corn-growing land to feed humans this way.

First consider the 1 hectare of corn that's grown in either of the two above scenarios. Some invertebrates will inhabit the corn fields, both as herbivores (such as pest insects on corn) and detritivores (such as springtails and mites in the soil). Presumably the numbers of these invertebrates will be similar whether the corn is grown for consumption by humans or farmed insects. However, insect farming gives rise to additional insects—namely, those being farmed. So it seems likely that total invertebrate populations are higher in the entomophagy scenario for this 1 hectare of land.

How about the other 1 hectare of land? Here we have to compare invertebrates on native vegetation vs. those on corn fields plus those created by insect farming. It's not obvious whether corn fields contain more or fewer invertebrates than native vegetation, but for the sake of argument, suppose we think corn fields contain many fewer invertebrates than native vegetation. I think insect farming would still increase invertebrate numbers because so much extra food would be eaten by invertebrates in the insect-farming scenario, as explained below.

Cain, Bowman, and Hacker (2008), citing "Cebrian and Lartigue 2004", report that "On average, about 13% of terrestrial" plant growth is eaten by herbivores (p. 436). I presume that most of the rest is eaten by detritivores. While there are many detritivorous invertebrates, most decomposition of organic matter is done by non-animals. Petersen and Luxton (1982): "The soil fauna appears generally to be responsible for less than about 5% of total decomposer respiration" (p. 288). So even if all plant herbivores were invertebrates, we would conclude that something like 13% + (100% - 13%) * 5% ≈ 17% of plant growth is eaten by invertebrates in a natural ecosystem.

Meanwhile, what fraction of vegetation is eaten by invertebrates in the case of insect farming? Tomasik ("Crop ..."), citing another source, reports that the harvest index for corn is 0.52, and the root-to-shoot ratio is 0.18. This means that for every 1 kg of aboveground corn crop, you get 0.52 kg of edible output, and there's also 0.18 kg of root mass. So the edible fraction of all plant mass is (0.52 kg) / (1 kg + 0.18 kg) = 44%. Since this edible corn food is fed to farmed insects, the fraction of plant growth eaten by invertebrates would seem to be at least 44%, not even counting the invertebrates on the corn fields. Since 44% is more than double the 17% number calculated in the previous paragraph, it appears prima facie that growing crops to feed to farmed insects significantly increases the fraction of plant production eaten by invertebrates.

Perhaps one could argue in response that farmed insects tend to be much larger than the mites, springtails, nematodes, and other diminutive invertebrates found in soils, so that even if insect farming increases the fraction of plant growth eaten by invertebrates, it's not clear if insect farming increases the raw number of invertebrates, if we count one tiny soil nematode on equal footing with one large farmed cricket. This may be, but I think larger invertebrates generally deserve somewhat more moral weight than smaller ones.

Appendix: Shellac

This discussion has moved here.

Footnotes

- Some people feel that moral weight scales roughly linearly in brain size. If so, then we might expect the total weighted suffering of insects to be roughly on par with that of bigger animals per unit of meat output, assuming a similar brain-to-body-mass ratio for insects vis-à-vis bigger animals. In fact, there are some reasons to think the direct-suffering-per-output ratio is higher for insects:

- Small animals like insects have more brain per body mass than most large animals, including humans.

- Large-animal meat may have more fat than insect meat, which implies more calories per kilogram.

On the flip side, the following factor suggests less suffering per unit output for insects:

- Large farm animals live many times longer than farmed insects.

Personally I disagree with scaling moral weight linearly in brain size. I suggest something closer to a square-root scaling, which more strongly weighs against eating insects. (back)